some thoughts on emergent technology and the future of education

Key Points

- The rapid advancement of AI, automation, and emerging technologies will lead to a structural labor market shift of 22% by 2030, requiring a fundamental rethink of education to better prepare students for specialized, high-skill careers.

- Educational models are too slow to adapt to these changes, particularly in fields like programming and AI integration, where automation is already reducing demand for junior roles. Schools that proactively integrate AI-driven learning and specialized coursework will give students a competitive advantage.

- While human educators currently provide unique value, AI is rapidly advancing in areas such as personalized learning, assessment, and even emotional intelligence. Institutions that fail to evolve may be displaced by AI-powered education models that offer superior efficiency and adaptability.

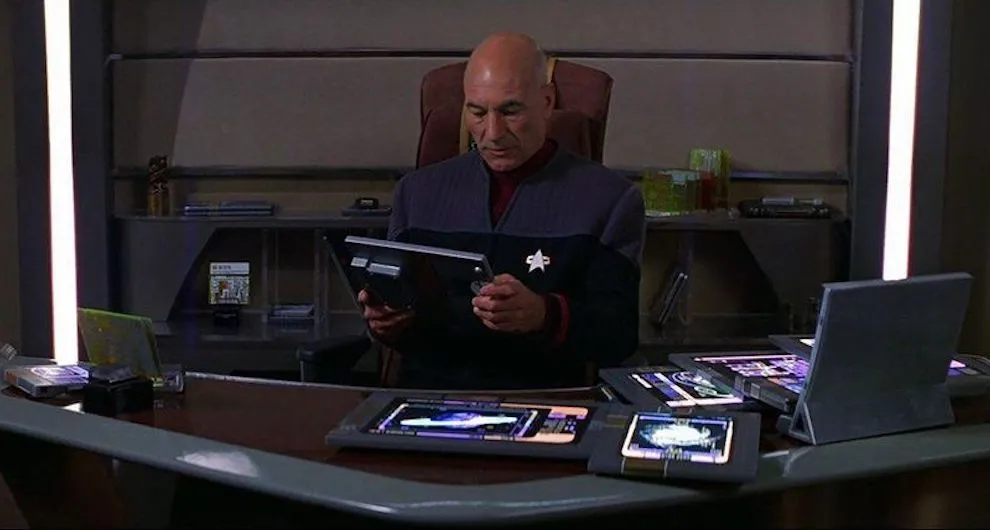

We often envision the future of technology by projecting today’s society forward, rather than considering how fundamentally different it might become. This tendency can lead to amusing images of hoverboards, like those seen in Back to the Future, or depictions of futuristic settings with outdated technology at the core, as in early Star Trek.

Are you a rich enough dude to own seven iPads?

Are you a rich enough dude to own seven iPads?

We currently stand at the horizon of another major transformation, yet I fear that we are making the same mistakes of not being bold enough in predicting just how different the future may look. My upbringing was marked by the internet revolutionizing communication and information distribution, and my generation had to learn a fundamentally new technology unlike anything before it, along with advances in computing, that reshaped the world. The next generation is going to have to learn how to interact and use emerging technologies, such as AI, robotics, automation, energy generation, and, I would add, VR and AR, in much the same way. These emerging technologies are expected to drive a structural labor market churn of 22% by 2030, meaning nearly a quarter of our labour market will look radically different to anything we know now, and in an astonishingly short period of time.

There is an optimistic argument that the jobs that are available to the next generation will simply change, but there is also the more pessimistic view that the availability of jobs may decrease as productivity becomes concentrated in fewer hands amid increasing competition over finite resources (if you ever want to make yourself depressed for an afternoon, I encourage you to go read Dr. Tim Morgan’s work over at Surplus Energy Economics). While I lean toward long-term optimism, I can’t help but foresee immense short-term turbulence as we grapple with restructuring labor markets—or even rethinking the fundamental economic structure of society. Emerging technologies will likely consolidate career pathways into a few, specialized, high-skill positions, much like how corporate and tech power has become concentrated in a few dominant entities. The white-collar clerical and service roles that once formed a large employment segment will shrink, and not everyone will find comparably paid work within their skill set. Meanwhile, blue-collar work will continue to be displaced as robotics installations replace an average of 1.6 manufacturing employees per machine, with many displaced workers unable to reskill quickly enough to secure new opportunities.

If we view workforce development as one of education’s societal roles, then I would go as far as to muse that most school curricula worldwide are not prepared for this impending labor market churn, and institutional inertia is causing adaptation to move too slowly. While education should foster holistic growth—building agency, willfulness, and determination—we must also seriously consider accelerating career specialization. Earlier exposure to specialized skills could help students navigate short-term economic upheaval and compete in a landscape that demands higher levels of competence. Traditional high school curricula should accelerate early specialization opportunities, such as creating courses that develop a deeper understanding of Machine Learning, Cybersecurity, Data Analysis, and Robotics, along with micro-credentialing pathways that allow students to gain recognized skills before university.

One example of an area that education is moving too slowly on is in considering the changes occurring in programming fields. The learn to code movement was driven in schools as a formula for success and job market opportunities that are likely to not exist anymore in the short term. Just five years ago the fields were populated with people who thought their occupational position made them special, unique, and indispensable…until they weren’t. Salesforce has announced that it will not hire any new software engineers in 2025. Google reports that 25% of its new code is AI-generated. Mark Zuckerberg has openly stated his intent to automate coding jobs this year. While AI will not replace the problem-solving capabilities of experienced engineers, the demand for junior developers will plummet as AI-assisted coding tools continue to improve. Computing courses in secondary schools must evolve accordingly, yet institutions are slow to react. The IB Program of Studies, for instance, still operates with outdated assumptions about future job markets and what skills students in these courses will need to be successful. Schools that implement accelerated learning programs and genuine AI-integrated coursework will give their students a massive competitive advantage.

The teaching profession is not immune to AI-driven disruption—perhaps not by 2030, but likely within my lifetime. If you are an educator reading this (though the following question could easily be modified for other professions, please feel free) I want you to deeply consider the following question;

What does my school, or my class, actually offer that is so unique that it can not be displaced by an infinitely patient, and much more broadly knowledgeable AI? What does it offer under how our society is currently structured, and what does it offer if we completely rethink the model of a traditional schooling day as we know it?

You’ve hopefully taken some time to think of some arguments. I would like to examine some of the common narratives I have heard in response to the above question. Imagine for all my counterpoints that the tools we have access to today will continue to get better (highly likely), and we can extrapolate some ideas off of some initial findings we already have.

- Human Connection: AI is already showing promising abilities in generating empathetic, well-received responses. Research by Hatch and colleagues found that AI-generated content is rated highly by therapists, often outperforming human professionals in perceived empathy. While AI may currently lack true therapeutic effectiveness (I generally find responses from ChatGPT to be too agreeable), these are the weakest versions of these tools—future advancements may easily overcome these limitations.

- Personalized Learning: AI tutors have demonstrated the ability to double learning efficiency in comparison to active learning classrooms, and had students feeling more engaged and motivated. In developing contexts, AI-powered after-school programs have resulted in learning gains equivalent to two years of education in just six weeks. I would not argue that these tools, as is, are a replacement for teachers. However, as AI tutors become more personalized and widely available, they could offer high-quality, cost-efficient education that outperforms conventional methods. How confident are you in your ability as an educator to out compete an infinitely patient, much more knowledgeable, and perfectly personalized AI teacher?

- Assessment and Grading: Previous Automated Essay Scoring (AES) systems have already matched human graders in accuracy and consistency while eliminating fatigue and bias drift. Studies have shown that human graders often have low inter-rater reliability, and even the same grader can be inconsistent across sessions. Technology driven grading tools offer quick feedback and are often perceived as more impartial or fairer than human teachers. Many of these technological tools were already exhibiting promise to replace human grading systems, and in the current AI surge, will be able to handle more complex tasks across a wider range of content areas.

- Extracurricular Opportunities: This assumption hinges on the belief that traditional schooling models—structured around a six- to seven-hour school day followed by extracurriculars—will remain unchanged. But alternative models already exist. For instance, South Alberta Hockey Academy runs four-hour academic days paired with four-hour hockey training sessions. They have been successfully running this program for years and, in my experience, working alongside people who came out of this program at my University were some of the most interesting and talented people in my classes. Imagine a future where AI-based education enables students to complete academic coursework efficiently, freeing time for personalized extracurricular pursuits tailored to their specific interests.

I strongly believe that the first prestigious secondary institution in each region to embrace a thoughtful emergent technology and AI-driven initiative to learning, both in person and across distances—where experienced teachers primarily supervise AI agents—will dominate the educational landscape. Just as technology has consolidated industries across sectors, AI will consolidate secondary education, rendering traditional schooling structures obsolete except for niche offerings.

I am purposefully being bold in my predictions, and only time will tell on how many of these ideas become reality, but I caution those who dismiss these ideas outright—they may be underestimating how dramatically the future will diverge from today’s expectations. Amara’s Law states:

“We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.”

As bold as some of these predictions may be, I fear I am still underestimating the long-term impact of AI on education. Those who are visionaries who are prepared to dream big, embrace, and adapt to these changes will have an enormous competitive advantage. Consider NVIDIA’s rise—over a decade ago, they positioned themselves as a leader in AI long before the technology became mainstream, and now, they dominate an industry almost entirely of their own creation.

The same principle applies to education. Schools and institutions that proactively, authentically, embed emerging technologies into their curricula will create students who are better equipped for the future. Unfortunately, too much energy is currently wasted on bureaucratic debates over AI policies rather than meaningful technological integration12. I witnessed similar waste when schools attempted to ban Wikipedia for research when I was a student—as we just used it anyway. The same is happening with AI. Instead of focusing on restrictive policies, we should invest in embedding AI into education in ways that build digital literacy and align with real-world technological usage.

While I have met individual educators who understand the urgency of these shifts, I have encountered only one institution (so far) that truly recognizes the depth of transformation needed. They are one of the biggest names in my field, and they have at least one person on staff who has the foresight to experiment with what the future of emerging technology in education should look like. Unfortunately, I won't be joining them for now (though I recently gave it a pretty good shot), but it was the impetus to me writing this post. I will likely share more specific parts of my visions for emergent technology in future posts, I cut out a giant section on the future of research, but I have to say the experience was a remarkable breath of fresh air to let dreams run free and envision what could truly be possible…

…and as far as I can tell, everyone else is going to be at risk of just watching

I am being intentionally strong armed with my usage of the word “wasted” here, because I do believe there are discussions to be had. One thing I always ask people is what actual measurable value does something like an AI policy bring? What problem does it actually solve?↩

Shortly after publishing this piece I decided to set OpenAI's Deep Research to the job of taking a look at the efficacy of technology policy in schools. I haven't gone into a deep look at it's sources yet, but it claims at the top that hardware policy is effective, while software policy generally doesn't seem to do much (and guess what category AI would fall under).↩